Dying with dignity: caring for Calgary's homeless at end of life

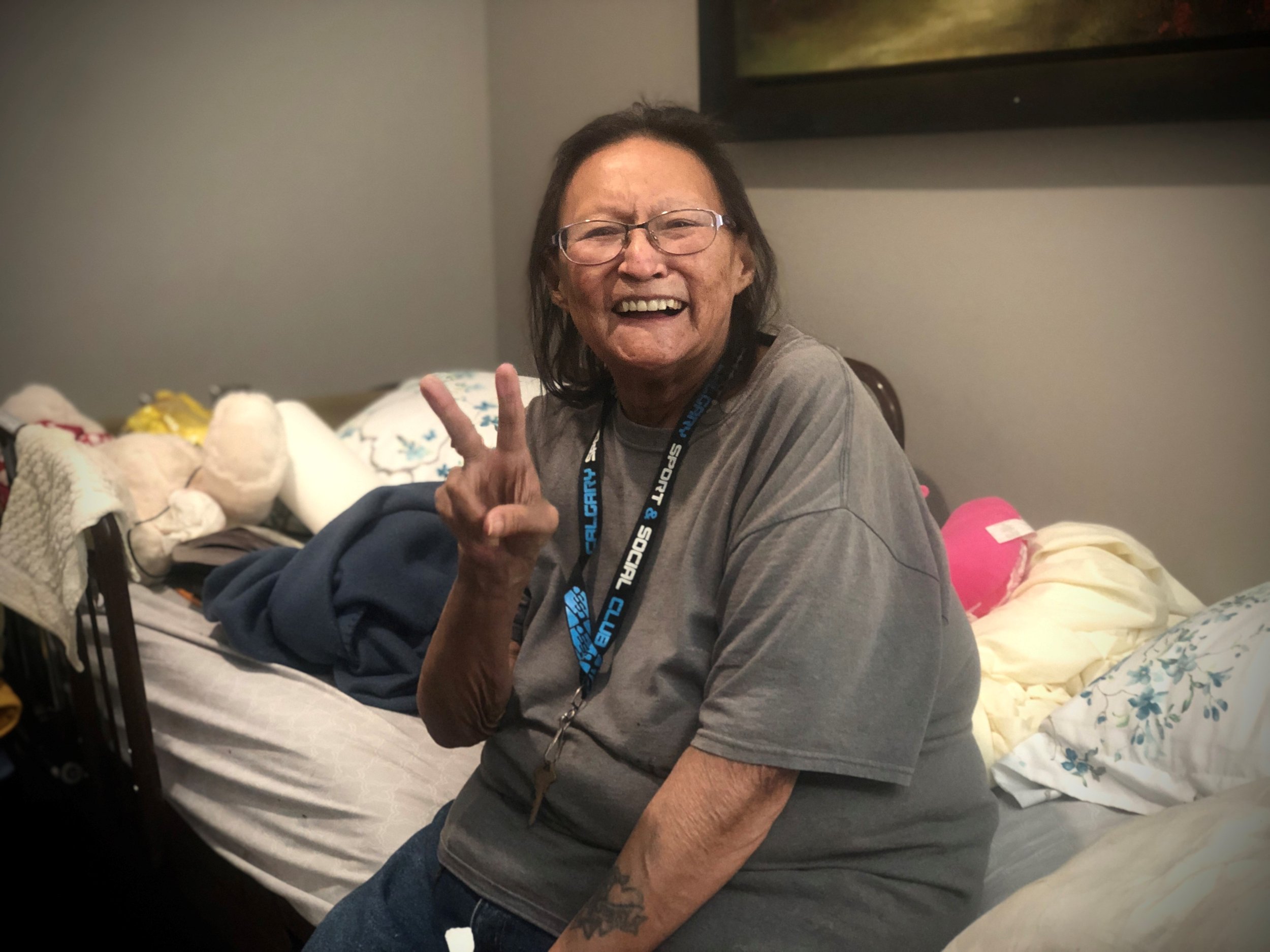

Violet Stonechild came to Murray’s house to die.

At 77 years old she was diagnosed with lung cancer, living on and off the streets in Calgary.

“I was homeless. Well, not homeless… I’d get a place with room and board, get kicked out or they raise the rent. You know, things were turning bad from bad to worse.” -Violet Stonechild

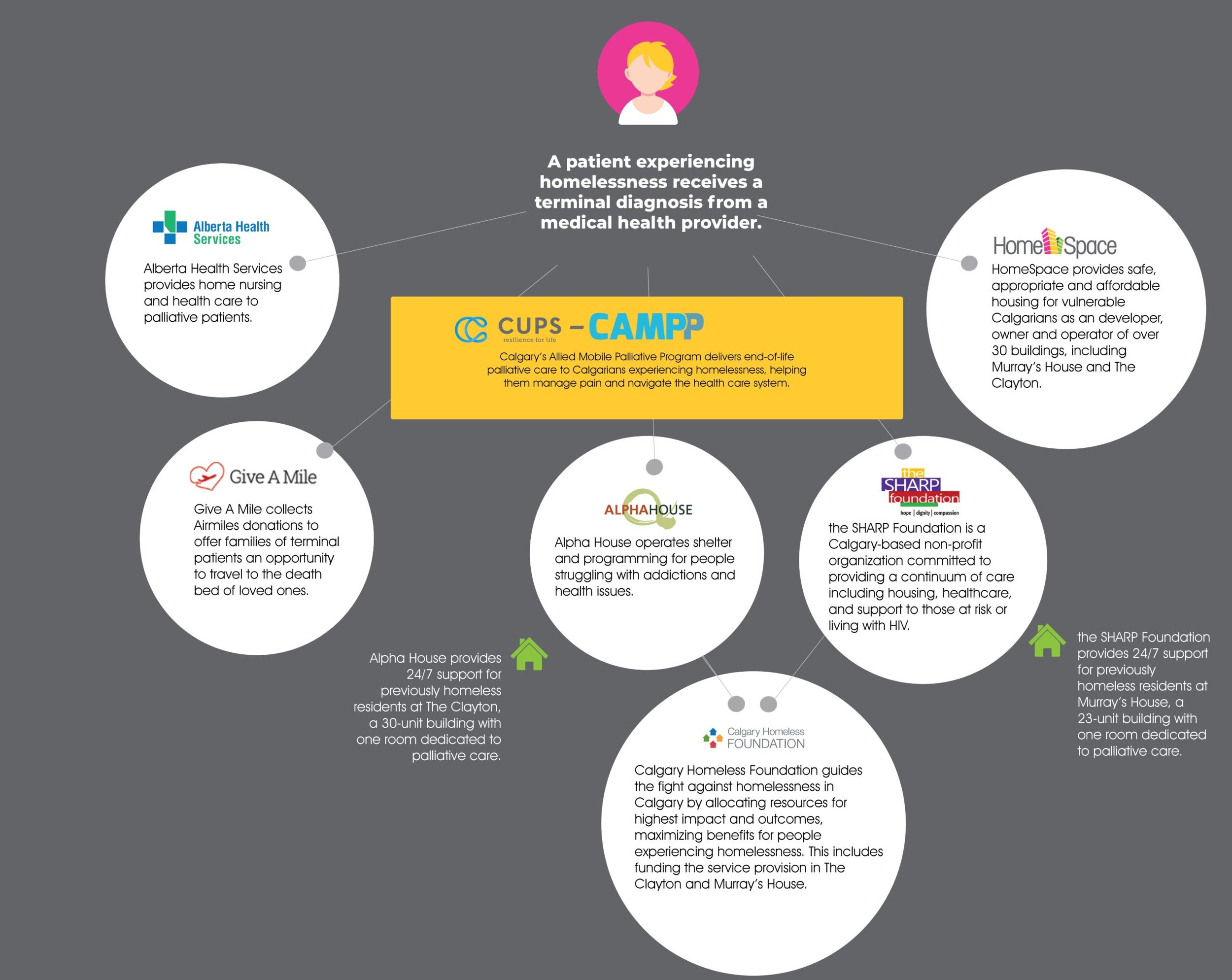

Workers with Calgary’s Allied Mobile Palliative Program (CAMPP) connect and follow up with people experiencing homelessness who receive a terminal diagnosis. CAMPP intervened with Stonechild, to get her somewhere safe for her final days.“A lot of traditional health care settings struggle to deal with people experiencing addiction or mental illness,” says Daniel Grover, a registered nurse with CAMPP. “When you have a population that's been so traumatized it's a different skill set to work with them.” There are only 2 palliative care units that cater specifically to people experiencing homelessness in the city. One is at The Clayton in Bowness run by Alpha House, another is at Murrays House run by The Sharp Foundation in South Calgary.

There are only 2 palliative care units that cater specifically to people experiencing homelessness in the city. One is at The Clayton in Bowness run by Alpha House, another is at Murrays House run by The Sharp Foundation in South Calgary.

These apartment complexes weren’t designed for hospice care. Built and operated by the HomeSpace Society, there are some accessible units in the buildings, but they were always intended for long-term supportive living - not end-of-life.

“We use a housing-first model at HomeSpace, which means taking people as they are and offering them the safety and security of their own private space. From there they can address the other issues that resulted in their homelessness,” says Bernadette Majdell with the HomeSpace Society. “First we provide housing then after that need is satisfied, health issues, addictions, and trauma can be addressed.”

Without these programs, the alternative for Calgary’s homeless approaching death is often the hospital or dying in the street.

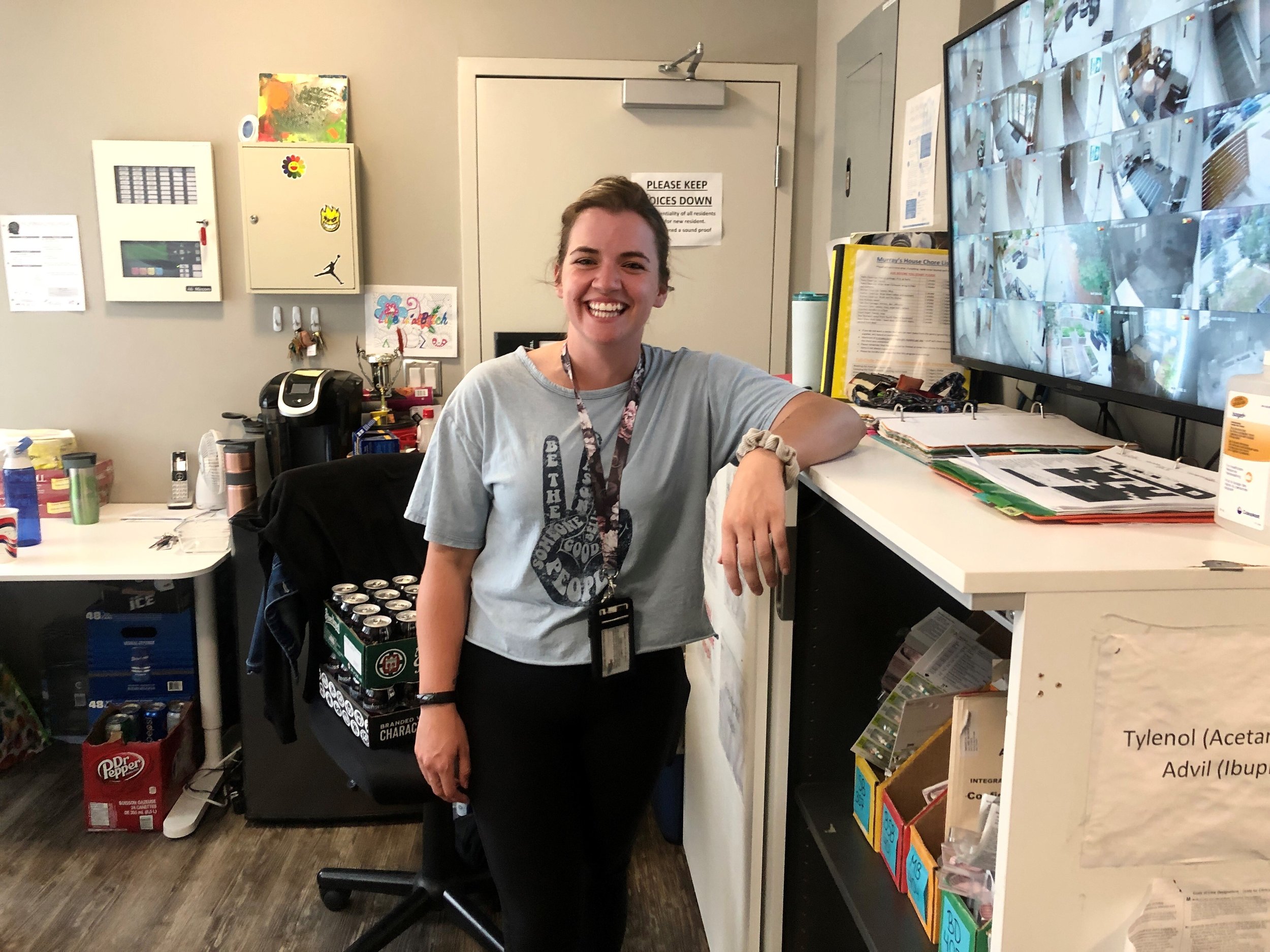

“Being able to provide someone the dignity and choice at end of life… everyone deserves a choice,” says Shaundra Bruvall with Alpha House.For fear of mistreatment, or due to dependence on alcohol or drugs, many people experiencing homelessness will delay seeking medical care and often have a lower life expectancy than the general population. That’s why Murray’s House and The Clayton approach palliative care from a harm-reduction perspective.

“Addiction is incredibly hard to overcome, and sometimes when you're near the end of your life, you don't really want to overcome it,” -Brianna Keats, palliative case manager at Murray’s House.

“So just having the supports 24/7, case managers looking after them, having the doctors come, nurses, they're incredible. Just coming and making sure that they're as comfortable as possible.”At Murrays House, Stonechild has an accessible private room, regular home health care from Alberta Health Services, and caseworkers that understand the complexities of caring for people struggling with mental health and addiction issues.At both Murray's House and The Clayton staff build bonds with residents and provide a warm atmosphere where people feel at home.“We have people that have time and work with residents one on one, not just providing basics and medication,” says Sarah Sandall, Housing Manager with Alpha House. “Hospitals aren’t fun, they’re noisy, you’re hooked up to things, it’s not your own space. It’s the ability to have your family come and create that in your own space”

This care takes incredible coordination between several organizations.

“Coordination among agencies is important because time is critical when offering palliative care. Agencies have different mandates and when people experiencing homelessness try to navigate these organizations on their own, their time in homelessness increases,” says Candise Latham, with the Calgary Homeless Foundation. “Coordination between agencies allows people to access resources more quickly, and Calgary Homeless Foundation provides the backbone for this coordinated effort through placement committee meetings that match people with the care they need.” After months in the palliative care unit, with a safe place to sleep, regular meals, and reliable health care Violet Stonechild has improved.

After months in the palliative care unit, with a safe place to sleep, regular meals, and reliable health care Violet Stonechild has improved.

“I've been I've been getting all good treatment, you know, they've been right on the ball. I'm not gonna give up yet, I’ve got grandkids to see.” – Violet Stonechild

Her health has improved so much that her medical needs have stabilized. Stonechild has reconnected with family and is now in long-term supportive housing at Murray’s House.She even dreams of getting her own apartment someday with a few friends.“Seeing her steps along her journey at end of life has been extraordinary,” says Murray's house LPN Troy Speechly. “I came in the other day and she's up in the kitchen making stew for the rest of the residents here. Whereas when I'd first met her, she was laying in her bed almost all the time and not really doing much else. Giving her that sense of community is so important.”While Stonechild’s cancer is being well managed, the palliative unit is always quickly filled with new patients. The needs for hospice care for homeless populations are great. Greater than two small units can currently handle on their own.While most major Canadian cities have a palliative program for people experiencing homelessness, Calgary lags behind.

Her health has improved so much that her medical needs have stabilized. Stonechild has reconnected with family and is now in long-term supportive housing at Murray’s House.She even dreams of getting her own apartment someday with a few friends.“Seeing her steps along her journey at end of life has been extraordinary,” says Murray's house LPN Troy Speechly. “I came in the other day and she's up in the kitchen making stew for the rest of the residents here. Whereas when I'd first met her, she was laying in her bed almost all the time and not really doing much else. Giving her that sense of community is so important.”While Stonechild’s cancer is being well managed, the palliative unit is always quickly filled with new patients. The needs for hospice care for homeless populations are great. Greater than two small units can currently handle on their own.While most major Canadian cities have a palliative program for people experiencing homelessness, Calgary lags behind.

“Demand in Calgary is quite high, and we know that there's a need, but we don’t seem to have enough beds to meet that need. So oftentimes, we're getting referrals from different parts of Alberta but we just don't have a place for them in Calgary.” - Stephanie Milla, The Sharp Foundation.

There is hope that such a program may be coming. The Sharp Foundation is proposing taking up residence in another HomeSpace property in Forest Lawn this winter. That would include rooms for 27 residents plus 24/7 health care for people facing homelessness that need end-of-life care.The key to creating the program is, of course, funding. A cost Milla says is justified.“It’s costing society quite a bit if we look at the taxpayer side. It costs a lot of money for people facing homelessness to access frequent emergency services,” says Milla. “By just providing basic needs: food, shelter… we can get people stabilized, it makes economic sense to fund these programs. And it’s the right thing to do.”For Stonechild, entering the palliative program at Murray’s House both extended and added richness and dignity to her life, and she’s not the only one.“We've had three or four people since I've been here who have been in that palliative room and have moved out of there and are doing excellent,” says caseworker Brianna Keats. “They have been told ‘you have X amount of time to live' and they've completely exceeded that amount… It's incredible.”